MEET THE ARTIST SPECIAL: Kroke from Poland

On the couch with Kroke

Of course, Kroke feels at home among the crocheted tablecloths and dusty windows of the classic cafes in the Jewish quarter of Krakow. This is where they have their couch, musically speaking.

The calendar shows February 23, 2019. Kroke will play a concert at home. Two venues in Kazimierz - the Jewish quarter - are central to their career, and Alchemia is one of them. The corner café is located opposite a former kosher butchery shaped like a diamond. At Alchemia, everything turns to gold. The kitchen serves delicious mezze, and through the door of a wardrobe you reach the smoking room, which is decorated with art.

Here in Kazimierz, halfway between magic and realism, Kroke became a band almost thirty years ago. Here they found their musical roots, and here they found their family roots.

Meanwhile, at more northern latitudes - in a winter-clad Sunnfjord that has days that are one hour shorter than Krakow - drifting Førdefestivalen and are preparing a wish concert for their own 30th birthday. They have asked people who they would like to hear next.

"We want Kroke," answered the vast majority.

- Really?!?

The three musicians in Kroke look at each other in surprise. Then they burst into joy.

- It's probably because of the effort we put in the first time we played. Førdefestivalen !

It was in 1998. They drove a rental car from a gig in Orkney and in a large horseshoe on the map, down through Great Britain and mainland Europe and up to Western Norway. They crossed both the English Channel and the Kattegat, but when they reached the Sognefjord, they saw the last ferry leaving the quay.

- We had driven something like 3000 kilometers, but would be late for the first gig in Førde the next morning. Because of a ... ferry, says Jurek, nicknamed Jerzy.

Double bassist Tomasz Lato, the band's undisputed GPS, came up with the map to find an alternative route around the world's longest, ice-free fjord. And he found it, in a way, via a private toll road where they paid in confidence in a mailbox. It was strange, they thought. And it was going to get more strange. On the way to the concert the next evening, the elevator door closed on Tomasz Kukurba's violin, destroying a tuning screw on the snail. He performed the concert, partly on the crushed violin and partly on a spare fiddle, 'the show must go on' and all that.

- But people felt so sorry for us that we felt sorry for them, they laugh.

When they were invited back to Førdefestivalen In 2010, they joked that it was probably like a band-aid on the wound.

- And the trick seems to work in 2019 too!

BlackStarJournal, Førdefestivalen our satellite in the folk music world, is constantly on our way to musicians' homes to get to know them. But what we didn't expect is that we would also get to know ourselves a little better.

The three Krakow musicians are genuinely fascinated by the trust that Norwegian society is built on. In fact, they talk about it at length.

- Even the Queen of Norway took us by the hand, they say with wide eyes. That's probably true. HM Queen Sonja was in charge of the opening of Førdefestivalen in 2010. She passed them in the lobby of the Sunnfjord Hotel upon arrival, so close they couldn't believe their eyes. Later that evening, she took their hands and looked them in the eye, one by one, before taking the stage as the festival's high patron.

- We have never experienced anything like it. We talked to everyone, and everyone talked to us. We made friends for life, they say, mentioning profiles such as Fliflet and Hamre and not least the Tindra trio with whom they recorded the album 'Live in Førde ' with.

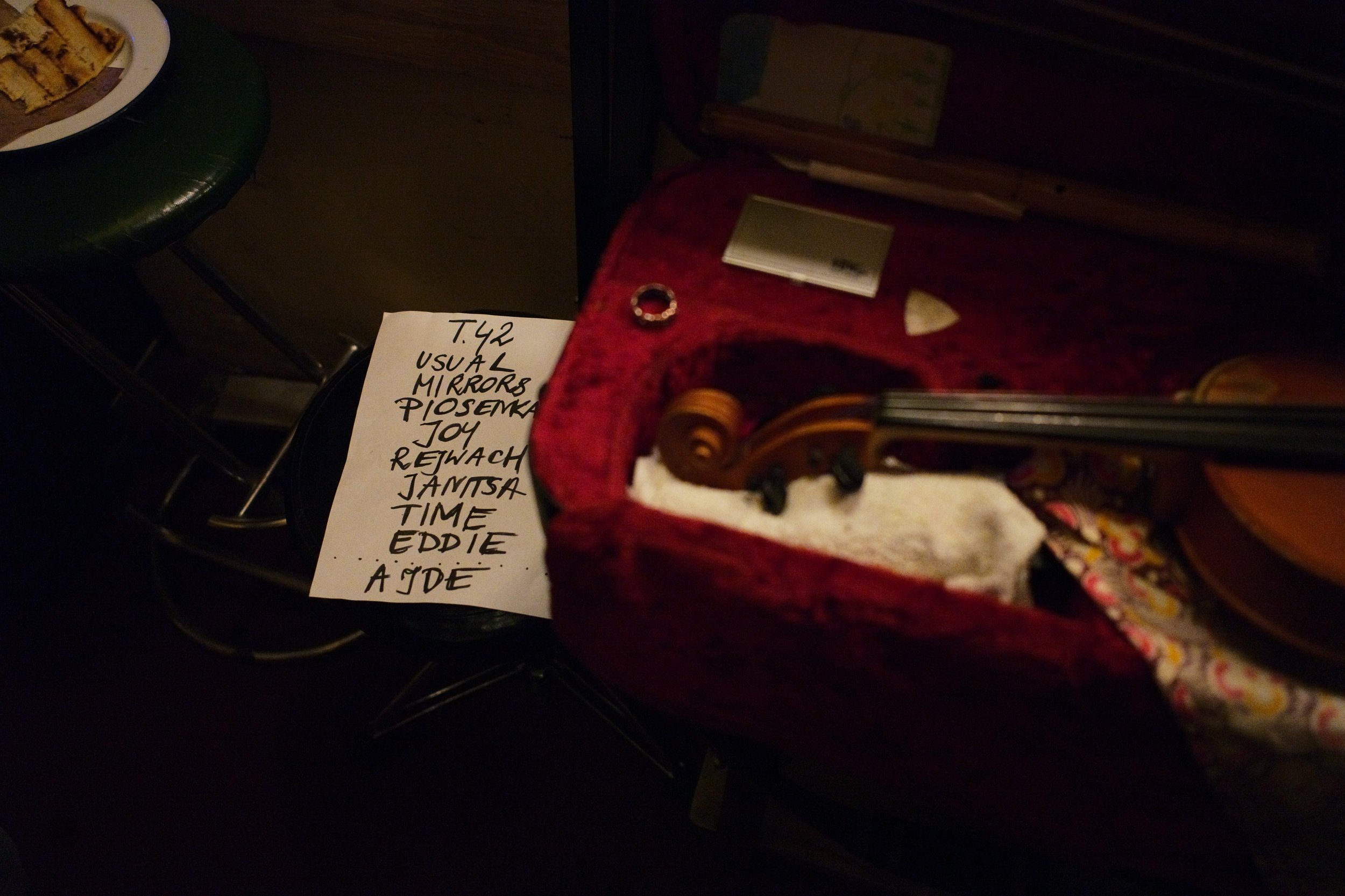

So what have they been up to lately? A lot. Right now they're putting the finishing touches on the recording of the theater music for 'Rejwach', based on last year's best-selling book of the same name, in which Mikolaj Grynberg takes the pace of modern-day Poland with stories about people who choose to both show and hide their Jewish identity.

In addition, they have recently released the long-awaited album 'Ser' together with Urna Chahar-Tugchi from Mongolia. The record is completely upside down in relation to what we think of as Kroke music. On the recording, it is Urna that gets to shine, as the Tindra trio also got to shine when they recorded an album with the Krakow musicians.

Kroke doesn't push through their own sound. They're more interested in exploring what happens in the middle, where the energy arises, between the musicians and the audience.

- For the three of us it's easy. We are free in music and have no boundaries. Improvisation is our language.

Sure, their music is klezmer, but it's also Sephardic, gypsy, classical and much more. In between the well-composed arrangements that Kroke is so famous for, something unexpected often pops up. A bit like finding a smoking room in a wardrobe. Maybe you could say they play out different dreamscapes?

What exactly is klezmer?

Ashkenazi Jews brought music from Eastern Europe and the Balkans with them when they immigrated to America, and across the pond the mix was dubbed 'klezmer.' But that wasn't the original meaning of the word.

A klezmer was a fiddler, in short. It was a professional title and more of a lifestyle, not the definition of a musical style.

- On the other hand, if you talk about Jewish music, you talk about 'fusion'. It is a mix of music from the rural areas where the Jews have stayed or traveled. Improvisation is the key, they say and continue:

- Through improvisation we look for new places, musically and mentally. When we get a response from the audience, then unexpected things can happen. The roots are important in the sense that it is good to know where you can find home again, back on your own sofa. From the corner of the sofa you can rather decide whether you want to go for another round, says Jerzy, pulling at his hair.

Sometimes in life you have to take a chance, and this was one of those times. It was the height of the Polish music scene, and the three music students wanted to go to cafes and drink coffee, but they were broke. They took to the streets. They lined up and played in the area around the medieval square in the hope of getting a few tourist kroner in the fiddle box.

Not only was it an expression of bad taste, but it could also have consequences for a classically trained musician to engage in 'busking' on the streets. One thing was that the doors to playing jobs and study places could close, but far more pressing: Would they be accepted by the gypsy fiddlers who were already making a living on the streets?

They agreed to take the legs on the neck, in case it was brewing for trouble.

- A large crowd gathered to listen. Suddenly we saw a gypsy boy pushing his way through the crowd. He came closer and closer and didn't take his eyes off us. We started to sweat. Then he elegantly threw 100 zlotys into the fiddle box, a small fortune!

"Not from you guys," the same guy replied when they later tried to give back in kind (only a little fewer of them).

It was there on the street that they were discovered by Sofia Łuczynska. She represented a new trend at the time and had ties to Ariel, a café and gallery that was about to open its doors in the heart of Kazimierz.

The combination of café and gallery is typical of Krakow today, but was anything but typical of the Jewish quarter at the beginning of the 1990s.

- Until then, the streets of Kazimierz were dark in the evenings, and cultural life was dead. But pretty soon we were playing at Ariel once or twice a week, as the first band after World War II.

Before World War II, Poland had the world's second-largest Jewish population. About a fifth of the world's Jews - more than three million people - lived within the country's borders. This changed fundamentally with Nazi Germany's genocide of the Jews, and of the few who remained, many were expelled in several waves of anti-Semitism, peaking in 1968-69.

It is uncertain how many Jews still live in Poland. Not everyone admits that they have Jewish blood, or knows it for that matter. In any case, it is less than ten thousand people. This article will not attempt to answer what everyday life is like for them in today's Poland, but a drive through the suburbs of Krakow reveals that things are hardly going smoothly. We see several graffiti with 'anti-Jew' and crossed out Stars of David.

Klezmer is not listed as the national folk music of Poland. Nevertheless, it is klezmer that tourists and others want to hear when they visit Krakow.

Polish folk music is described as dance songs and ensemble playing. The national dances, including the polonaise and mazurka from the 16th-18th centuries, are widespread beyond the country's borders. An offshoot arose in Sweden under the name polska, in Norway pols.

"History has a tendency to be harsh on folk traditions. There are still regions in Poland where people have an identity that is closely tied to traditions, but I myself am afraid that we are heading in the same direction as, for example, Germany, where folk music has more or less disappeared," says Jerzy.

It was at Ariel that Thomasz K. learned about his Jewish roots. His uncle came and listened to them.

"Do you know why you're playing that music there?" asked the uncle.

- Because I like it.

- And why do you think you like it?

The uncle could tell that his grandfather was Jewish, but that he had closed that door to family history for good when he was young.

- I'm glad to know, but it doesn't change my life in any way, says Thomasz K.

Thomasz L. says the same thing. He is well aware that his grandmother was a gypsy, born in Poland to parents from Hungary.

We look over at Jerzy.

- He's just an accordion player. A whole different breed, he bullies the others.

Slik Kroke music is its own genre.

Text, Video and Photo: BlackStarJournal